The Alien Quadrilogy

This series of films, begun in 1979, has been incredibly influential in science fiction, not least because of its central heroine, the redoubtable Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) who has battled her seemingly inexorable foe across three hundred years and four films. Four very different directors have offered their own spin on the basic "Jaws in space" concept of the original. The plot of each one is simple. There is a threat to an isolated community. That threat picks off members of that isolated community, one by one, until there is a final climactic showdown, led by Ripley, who kicks its ass. The end.

All around the edges we have the harsh, corporate world of the Company, the dissatisfied workers who find their personal safety compromised in the name of "bioweaponry", spaceships full of dull metal and fluorescent lighting, the relentless human colonisation of planets- a future that is mundane, harsh, unromantic and as far removed from the fantastical creatures of the STAR WARS series as you can get. This is very much science fiction for adults. We are presented with two living species only - the aliens, and humans, and, as Ripley says in Aliens, "I don't know which species is worse. They don't fuck each other over for a percentage." The only other creature encountered is the fossilised behemoth seen on the ship at the beginning of Alien. The humans we encounter are just as much Drones for their Queen, the Company, as the aliens are for theirs.

— Dallas in Alien

In additional contrast to STAR WARS, the Alien saga is a creative property that has been passed from hand to hand, with very different teams working on each installment, and bringing their own identity to their entry. Ridley Scott and James Cameron are both primarily action directors - with Scott at his best when depicting hand to hand battle between underdogs (The Duellists, Gladiator, Thelma & Louise) and Cameron best at all-out special effects firepower. David Fincher likes to un-nerve audiences, denying them the happy endings they want (Se7en, The Game, Fight Club) and in his chapter works exclusively with his trademark rust-tinged palette. Jeunet's humour is dark, European, brutal yet cartoonish (Delicatessen, The City of Lost Children). The one constant has been Weaver - who, despite being a fine actor with numerous and varied appearances under her belt, has never been more iconographic than as Ripley. Her vital screen presence is perhaps one reason why the excellent William Gibson script for the third installment was rejected - Ripley is in a coma throughout his version.

Stylistically, the films have done much to construct and develop genre paradigms, shaping what we understand to be the scenery of the future. Alien draws its mise-en-scene in equal measure from 2001:A Space Odyssey and Star Wars - Kubrick's sleeping pods, his omniscient, environment-controlling computer ("Mother", in this case, not HAL), walls of diodes etc are tempered by Lucas's representation of the future as "used". The Nostromo's landing ship's exterior owes much to the Millennium Falcon - shape, landing gear, perpetual need for repair - while the fluorescent-lit interiors are pure Kubrick.

It is testament to the creativity of the original idea that this simple formula has provided such a fertile ground for revision, and has manifested across different media forms. An elaborate mythology has been developed and explored in the Alien vs. Predator computer games, and interest in the series continues to make it bankable (with the two Alien vs. Predator movies making respectable, if not spectacular, coin). The video game community expressed an interest in an Alien Vs. Predator action RPG game that was in its final stages of completion before the project was canned. As these movies continue to be a SciFi hit we still may see the action game come back to the market for multiple gaming consoles.

The Alien series — including the "related" Prometheus — is science fiction at its best: dramatic, human, perfectly realised and chillingly plausible to anyone who has had to contend with cockroaches.

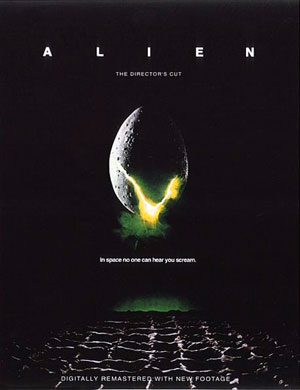

Alien (1979)

In space, no one can hear you scream

Alien was apparently described in the early stages as a haunted house movie set on a spaceship. This chillingly simple idea is explored to great effect by Ridley Scott, in only his second major studio movie. The mining ship Nostromo - a nod to Joseph Conrad - is diverted from its homeward flight by a distress signal. They land on a seemingly deserted planet (known only as LV-426) to discover that the distress signal is coming from a ship that is very old, containing the fossilised remains of some alien race. Too late, Ripley deciphers the signal as a warning, not a distress call.

This is a successful shift of the archetypal narrative paradigms of a traditional horror movie. A small group (the Nostromo's crew) are lost in the deep dark woods (space, and the atmosphere of LV-426) when their car (ship) breaks down. They go to the nearest sign of habitation, a seemingly deserted house (the crashed, fossilised spaceship), and, while the entire audience is screaming "Don't go in the basement" the most foolhardy member of the group (Kane) goes poking around where he oughtn't, and awakens a Sleeping Threat. The narrative is pure horror, only the mise en scène dictate this is sci fi. Scooby Doo, where are you?

In lesser hands, Alien could have been just a slasher-in-space flick but the film-makers elevate the material far beyond B-movie status, incorporating ideas and themes from a range of sources. The enormous space ship carrying twenty million tons of mineral ore is named The Nostromo, an explicit acknowledgment of Joseph Conrad's influence, also echoed in the quotation from Heart of Darkness at the top of the screenplay (“We live as we dream, alone.”). Scott's first film was based on one of Conrad's short stories, and in this piece also, the film director weaves the novelist's preoccupation with evil, loneliness, and the remorselessness of nature into his storytelling. Whilst Conrad's characters sailed up uncharted African rivers in the name of Empire and Capital, Scott's crew venture into computer-vectored space, but are equally far from civilization. Despite the centuries and technologies separating them, the conclusions drawn about humanity are the same: we are an avaricious, pitiless species capable of perpetrating great horrors.

—Joseph Conrad Under Western Eyes (1911)

The Xenomorphs in themselves are not evil, but their savagery exposes the beast within the humans. Both the Company and the crew are driven by mercenary greed (Brett and Paker harp on about "the bonus situation" and getting "full shares" in the discovery of the creature), and it takes only a heartbeat for the humans to turn hunter-killer when threatened. Sometimes the Monster Within is as terrifying as the one snarling outside the door.

The first hour of the film is a slow build up of tension: the petty squabbling of the crew, the claustrophobia of the Nostromo, the bleak landscape of LV-426, the seemingly false alarm of the discovery of the face-hugger and its temporary attachment to Kane (John Hurt). Yet from the chest-bursting scene onwards (surely one of the most original and gory concepts in modern cinema? Legend has it the cast were not told what was going to happen during shooting that day, so their shock is genuine) the movie is a demented chase sequence, with the speedy, horrific realisation of what they are up against dawning on us and the crew. Not only does this monster have acid blood ("your bullets cannot harm me!") it grows like a mushroom ring, quickly evolving from penis dentata to evil mofo with claws and a tail. Its growth rate is phenomenal: chestbursters - which are a foot long at most - appear as drones just a short time later, growing jointed limbs, a chitinous exoskeleton and a mouthful of teeth in around 4 hours. The crew scream very loudly but no one can hear them. No one will help them. It is this last realisation that turns Ripley, a previously rather grumpy flight officer, into the finest hero space has ever known.

Ripley was a man in an early draft of the script. The decision to turn her into a woman - and to cast a relatively unknown stage actress in the part - has been one that has had 20th Century Fox laughing all the way to the bank ever since. Ripley begins as a cynical middle manager. She is not particularly to loyal to the Company who keeps her away from her daughter's birthday party, but she gets on with her job. She is one of those heroes who has greatness thrust upon her, as those further up the chain of command get chomped. Her cynicism is tempered with compassion, and she displays a gift for military strategy when under pressure. Ripley vs. Alien (in any form) is a perfect balance between protagonist and antagonist. She is as fierce as her foe, as lithe and graceful and sinewy, as intensively protective of her own, stronger mentally but weaker physically, as absolutely dedicated to her goal (interestingly, hers is destruction, theirs is reproduction). We love Ripley for many things - she is the only one seen cuddling the ship's cat, Jones for a start. She begins as a Company lackey, refusing to open the hatch when it appears that the Thing attached to Kane's face might contravene quarantine rules. When she is over-ruled by Ash, she protests, but is powerless to stop him from countermanding her order. He is the one with his finger on the "Open" button of the door, after all, and she is a woman. Yet it is when Ripley relinquishes the rules that she becomes a hero. She is the only character, throughout all four films, to consistently trust her instincts. Her instincts are the same as the audience's: "Let's get rid of it". What is most appealing about Ripley is her ability to reduce situations to simple binary opposition (live/die, friend/foe) and act accordingly. When there is ever any suggestion that it might be valuable to keep an Alien alive (and let's face it, there should tend to be at least SOME discussion over whether or not it is moral to blow another species entirely off the face of the universe) Ripley is unequivocal in her "No!" She despises what she sees as weak decision-making in the characters around her, especially when she has to pick up the pieces from some poor call made by a superior. Ripley is a kind of Everyworker, just doing her job, until the ridiculousness of corporate thinking causes meltdown. Ripley breaks free of the hierarchy to do things her way - in all 4 films she is never initially the 'official' leader of the group - and her way, stark and destructive though it is, is always the right way, indeed the only way, for survival.

Ripley's final confrontation with the alien on board the Nostromo shows her clad in a space suit (lessening that physical inferiority) and forcibly ejecting it through an airlock. She births it into a void, and watches it spinning away: brutal motherhood.

Ripley is not the only memorable character in the movie. Weaver has an extremely strong supporting cast of fine character actors - Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt, Ian Holm et al. Their performances provide a chilling gravitas that lifts the movie out of the B-zone - they are not a bunch of nubiles alone in the woods whose one-by-one demise we whoop. They are rounded and real, effectively conveying boredom, anxiety, paranoia, bad habits (these people smoke at the dinner table! while others are eating!), vague undercurrents of sexual harrassment and stark staring fear. Very much like any present day workplace.

Stylistically, Ridley Scott draws heavily on 2001: A Space Odyssey, particularly for the exterior shots of spaceships, and for the silence which accompanies some of the film's key moments. The sequence where Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) goes (alone!) to look for the ship's cat, Jones, is as slowly paced and suspenseful as anything in The Shining, released the same year. Brett pads from room to room, calling out "here Kitty!" through the rusted interior of the Nostromo. A series of close-ups give us his face, denying us what might be lurking in the surrounding shadows. As a savvy audience, we know he's going to get his, he has spilt off from the main crew and is wandering into the half-darkness. Every time the shot changes we expect to see an alien reaching for his jugular, especially after he finds a sloughed alien skin. However, like, Kubrick, Scott extends this sequence to its maximum time limit - Brett bumbles about, not mirroring our concern. He spends what seems like forever cooling his head and face underneath a water leak. The only sound is a diegetic throbbing - the mechanical heartbeat of the Nostromo. He's looking for a goddamn CAT. Only when our nerves are stretched to breaking point does Brett finally find Jones. Who hisses. Not at Brett, but at the gleaming, looming figure of the Alien, larger and more terrifying than before, appearing exactly where we have expected it to all along, over Brett's shoulder. Brett is taken, silently, his cries soon muffled, and we are left with a close up of the cat's impassive face, pupils contracted, one predator

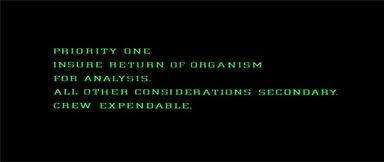

Scott also looks to 2001 for his space machinery paradigms. The hi-tech parts of the Nostromo are direct echoes of what Kubrick decided a spaceship should look like - all gleaming white interiors with flashing lights. The dining room, the central computer room, the hibernation pods, are all straight outta 1968. But the Nostromo also has a dark side - a full manifestation of Lucas's concept of "used space". Beyond the central whitely lit areas (ie where the alien hides and crew must go to find it) the Nostromo rusts, drips, echoes, creaks, decays. Mother, the omnipresent computer entity that controls the ship, is probably a HAL 10000. Mother, like Hal, sees all, knows all, and acts strictly according to her programming. Mother and Ash between them represent the power of machinery over humans - especially when that machinery is owned and programmed by The Company and serves profit over human interests. When Dallas (Tom Skerrit) requests help with dealing with the alien from Mother, the response is negative ("Insufficient data"."Does not compute"). Ash, as Chief Science Officer and resident paranoid android, is similarly unhelpful. He too does not compute the humans' chances of survival - they are so minimal as to be negligible. Even with his last bubbling breath he cannot offer a secret key, any kind of get out clause to the crew.

Ripley: Ash, can you hear me? ASH!

Ash: Yes, I can hear you.

Ripley: What was your special order twenty-four?

Ash: You read it, I thought it was clear.

Ripley: What was it?

Ash: Return alien life form, all other priorities rescinded.

Parker: What about our lives, you son of a bitch?

Ash: I repeat, all other priorities rescinded.

Ripley: How do we kill it?

Ash: You can't.

So, despite being surrounded by hi-tech gadgetry, the crew are on their own, eventually resorting to the cave-dweller's favourite, fire, to battle their foe.

Aliens (1986)

Whereas Alien was a horror film set in space, Aliens is a Vietnam war movie thus transplanted. And, while it lacks the claustrophobic complexities of its predecessors, it's also probably one of the best action films ever made. Cameron, ever conscious of his B-movie Roger Corman roots, cranks up the tension to a near-unbearable level and keeps it there. This movie has everything - a love story, comrades-in-arms a little girl lost, a very haunted house, serious weaponry and MORE aliens.

The crew of the Nostromo all perished battling one Xenomorph. When Ripley booted it into space, there was a solid sense of closure, and she and Jones the cat could sleep soundly all the way home. Her final, expressed desire is that she will float around in space for approximately six weeks before someone picks her up. Aliens gears up its narrative by crushing even that hope for its protagonist, and begins some 57 years later. Ripley's frozen ship is finally salvaged, and she is returned to a life where all the people she knew and cared about are gone, and only The Company (now identified as the Weyland-Utani Corp.) remains. It promptly takes her to court for blowing up the Nostromo, and she is stripped of her flying credentials. They claim not to believe her tale of deadly xenomorphs, and scoff at her claims that LV-426 is dangerous ("there have been people living there for twenty years"). In parallel to the first movie, Ripley's warnings are ignored in what the Company thinks are its best interests.

From the outset, Ripley articulates anger and defiance, but like some old-time fire-and-brimstone preacher, no one wants to listen to what she says until it is too late. Act One sees her represented as the disenfranchised outcast, her return to civilization causing something of an embarrassment. Despite her skills and experience she is reduced to working down at he cargo docks, dispossessed of status, identity, well on her way to becoming a Space Age Ancient Mariner.

Cut to Burke, the corporate bagman, asking Ripley for help. The terraformers (in scenes replaced in the Special Edition) have found the alien nest (they were alerted and sent by Weyland-Utani to investigate, natch) and all contact with the colony has been lost. He offers Ripley a job, reinstation. She has no option really to accept, or resign herself to a life operating forklift trucks. We see it in her eyes, she wants adventure, she wants authority. Like some haunted 'Nam vet, she is drawn to revisit the scene of her moment of adrenalin, and finds herself returning to LV-426, as an "advisor", on board a reconnaissance craft (the Sulaco), with a bunch of pumped up Space Marines. And lots of guns. Lots of guns.

The Sulaco itself looks like a huge gun, priapically probing its way through space. Its crew are no less phallic; upright, with lots of gadgetry attached to their heads. As with Alien, the crew, thanks to Cameron and some fine performances, emerge as individuals, rather than merely xenomorph fodder. This is contrary to the generic conventions of science fiction, or horror, yet it tallies with those of a war movie, where the buddies' identities become crucial to our understanding of the plot, and our predictions of the order of their ultimate demise.

Ideologically, the film prefigures the revisionist Vietnam movies of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The pumped up, technologically superior marines are no match, despite their sophisticated gadgetry, for a simple organism, frequently likened to an insect. Initially they are derisory about "another bug hunt". but their derision turns to fear (Hudson:"Now what the fuck are we supposed to do? We're in some real pretty shit now man... That's it man, game over man, game over, man! Game over!") and they are picked off, one by one. The generic conventions of a war movie are plundered, from the rookie lieutenant whose indecisiveness and inexperience costs lives, the cigar-chomping sergeant who waxes sarcastic about "another glorious day in the corps!" We see the soldiers succumbing to naked terror, as they realise that none of their weapons, or their training, or their attitude can ever really prepare them for meeting death face on.

The lone survivor of the LV-426 colony is a terrified young girl, Newt (Carrie Hinn), who solemnly tells Ripley that the excessive weaponry "won't make any difference" come nightfall. She has survived, as little girls throughout the ages have survived, by hiding in corners and hoping she won't be noticed - she has used a network of air conditioning and waste ducts reminiscent of the Cu Chi tunnels employed by the Viet Cong. She represents an entirely different set of human capabilities to the soldiers, a guerrilla fighter as opposed to their ground force. She is resourceful, humble, smart, and, most importantly, determined to avoid open confrontation with the aliens - history repeatedly suggests that this is the only way to defeat a superior force. A movie focusing on Newt's kind of survival techniques might not have struck box office gold in the way this shoot-em-up explosion fest did, but her presence in this narrative balances out the testosterone highs. Newt is also the wronged innocent, a character the others can sacrifice their lives for, and achieve a certain kind of nobility and redemption in doing so.

Alien3 (1992)

Production of the third instalment in the series was beset by problems from the get-go. It was originally conceived as a two-parter, focusing on Hicks as a central character caught in the crossfire when Weyland-Utani square off against a separatist group of humans. Ripley would have been reduced to a minor role - a move originally approved by Weaver, who felt that the character had done all she could to battle the beasts. Thus began a tortuous process of development, with the script passing through the hands of several writers (including William Gibson) and directors (Renny Harlin...), before beginning production at Pinewood Studios in the UK, with David Fincher at the helm and an unfinished screenplay - producers Walter Hill and David Giler finished the job themselves. Rightly or wrongly, 20th Century Fox president, Joe Roth, felt that Ripley was the franchise, and was unwilling to greenlight an entry without her.

The result was a disappointment to many, although given time, and a lower set of expectations, it is still an interesting movie. Fans felt cheated out of another a gung-ho war movie, a reprise of Aliens with Corporal Hicks and Ripley leading yet another charge before sailing off into the sunset. However, it is a very thoughtful piece of film-making, intertwining the conventions of a prison movie with those of science fiction, and boldly killing off a major character in the process. It has Fincher's fingerprints all over it - unremitting gloom, orange hues, long, confusing sequences, biblical undertones and a wilful determination to defy audience expectations - just like in Se7en, Fight Club, and Panic Room. It has Weaver's most powerful performance to date. But audiences hated it. The box office figures speak for themselves - on a budget of $50M it only grossed $55M in the US, according to IMDb. Compare that to Aliens, with a domestic gross of $81M on a budget of $18.5M.

The movie has some definite strengths.Weaver turns in her strongest performance as Ripley, daring to show a character driven to the point of madness by the near-Biblical suffering she has endured. Her shaved head emphasises Ripley's vulnerability, there is no hiding behind her trademark curls on her slow slide to the edge of the abyss. She is at once snarling and sexual, lurching from attempted rape to the arms of Charles Dance. No making eyes at Hicks as he coyly wipes his weapon here. She is as intense and instinctive as ever, with her final sacrifice counting as one of the most moving moments of 90s sci-fi cinema. Her emotional torment is played out against a backdrop of rust-eaten isolation — the prisoners are so far removed from the centre of society that they have lost all sense of who they are and how they should behave. Fincher plunders his experience as a music video director, and cranks up the atmosphere with cut aways - from candles being blown out, to Newt's eyelash during the autopsy. There are truly great moments to the film - like the funeral, where the bodies of Hicks and Newt are committed to the furnace. Dillon's impassioned speech ( "For within each seed, there is a promise of a flower, and within each death, no matter how small, there is always a new life. A new beginning.") is given dark resonance by the cuts back and forth from the Rottweiler giving a new beginning to a chestburster. Great cinema. The autopsy of Newt is also harrowing, shots of bloodied surgical instruments in a bucket signifying the final violation of this poor child. The romance between Clemens (Charles Dance) and Ripley is intriguing - but then he gets eaten.

The weaknesses are jarring and confusing. Creature effects are at the heart of the series, and this third entry failed to live up to the standards set by its predecessors. Audiences thrilled by the hordes of rampaging Xenomorphs in Aliens were not impressed at the reversion to a single creature on the loose, especially as it is rendered as a rather cartoonish, overly green rod puppet, that fails to move in a convincing way. It repeats the same actions over and over again — i.e. it whips speedily across the ceiling of a corridor and bites a prisoner's head off — and quickly becomes predictable, rather than scary. The alien POV camera is good, however. There is a rampant sense of confusion throughout the prison. The action lacks geographical pointers (all the corridors look the same, and we have no clue how close one location is to another nor how much of a threat the Alien represents at any given moment, including during the plan to "close the doors" in Act Three). The previous movies showcased solid supporting characters, with crews consisting of a range of ethnicities, and both genders. Despite the fact that there are some fabulous character actors present (Postlethwaite, McGann), it's difficult to empathize with individuals as their shaven heads and uniforms make them all look the same (especially after they have been sprayed with blood). The introductory sequence, showing them trying to rape Ripley, doesn't endear them any to the audience either — the net result is that we don't really care when or how they die. Instead of rooting for the prisoners against the Alien, we resign ourselves early on to the fact that they are all doomed.

- A critical review from Arrow in The Head

- Positive, revisionist review from Inkpot.com

- The Script (Hill/Giler version - the one that got made)

- William Gibson's version of The Script.

Alien:Resurrection

Witness the resurrection.

- The Script

- Salon.com - Return of the Vagina Dentata

Useful Links

Do you know more than you should about the Aliens? I do.

- The Anchorpoint Essays - know your enemy - intensely detailed account of the Xenomorph's life cycle

- Alien Movies Resource Page

- Alien Lair 2000 - spooky b/w site

- Xenomorph.org - full of Alien collectables. Impress members of the opposite sex...

- H R Giger - a look at the German surrealist's work

- Title Sequence Analysis - comparison of each of the quadrilogy films